There is Hope for your Future

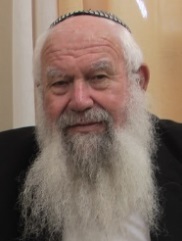

הרב זכריה טובי

ראש הכולל

The Midrash relates (Eicha Rabbati, Intro. 24) that when the Temple was destroyed and Israel were exiled from their land, our matriarch Rachel rose before G-d and pleaded before Him regarding the exile of Am Yisrael. Immediately, G-d's mercy was kindled, and He promised her that He would return Am Yisrael to their place, as it says in Yirmiya (31:14):

Thus said Hashem: A voice is heard on high, wailing, weeping of tamrurim (lit., bitterly), Rachel weeps for her children; she refuses to be consoled for her children, for they are gone.

Yirmiya continues (31:15-16):

Thus said Hashem: Restrain your voice from weeping and your eyes from tears; for there is reward for your accomplishment – the word of Hashem – and they will return from the enemy's land. There is hope for your future – the word of Hashem – and your children will return to their border.

What does, "weeping of "tamrurim" mean? The word tamrurim is from the word, tamrur – a road sign. The crying of Rachel is a weeping that has a destination; it is a weeping about the future of Am Yisrael. Rachel does not cry over the past destruction; Rachel cries in order to take Am Yisrael from the darkness of the exile and return them to their border – to Eretz Yisrael. G-d answers her, indeed: "There is hope for the future ... your children will return to their border." Rachel's weeping was able to influence and arouse mercy on Am Yisrael. The goal of crying is not out of despair about the past, but rather tears have the power to build the future and the hope of Am Yisrael.

Thus, the Rambam writes (Hil. Ta'aniyot 5:1): "The fasts over the destruction [of the Temple] are a remembrance of our bad deeds, and the deeds of our ancestors, which were like our deeds now ... Through the remembrance of these things we will repent to do good." The goal is not the mourning itself, but rather the goal is for the improvement of the future – that we will return to do good, and thereby build the Temple.

This is what King David taught us (Shmuel II 12:16 ff.). When his son became deathly ill and was about to die, King David fasted and slept on the floor and cried bitterly. However, when the child died, David got up from the earth, anointed himself and observed seven days of mourning. His servants were perplexed and asked him: When the child was still alive you fasted and cried, and now that he is dead you stop? David answered: When the child was sick, I fasted and cried because I hoped that G-d would annul the decree. Now that the child is already dead, there is no longer any reason to fast and cry, because he will not return to me until Resurrection. This means that the whole nature of mourning, of crying and of fasting is the hope for the future. We thereby pray that G-d will build the Temple, and we have the power to bring it back and to correct what we damaged.

Megillat Eicha concludes with the verse: "Even if You had utterly rejected us; You have sufficiently raged against us." (5:22) Why does Megillat Eicha end with words of calamity, as the Prophets almost always end with something good, with words of praise and consolation? Indeed, in order not to end with calamity, we repeat the next-to-last verse, "Bring us back to you Hashem, and we shall return, renew our days as of old." (5:21) Nonetheless, why does the Megillah not end with this verse?

However, the Midrash says:

R. Shimon b. Lakish said: If, "You have utterly rejected us" – there is no hope; "You have sufficiently raged against us" – there is hope.

This means that if G-d were simply to reject us – there would be no hope for Am Yisrael. However, when G-d rages against us and brings upon us suffering – there is hope, because G-d wants us to repent, and, as a result of this He will renew our days as old. Therefore, our conclusion in repeating, "Bring us back to you Hashem" – is the outcome of the end of the last pasuk, "You have sufficiently raged against us," because the goal of the anger is that we should repent.

These days are ones of crisis – both in the historic and the immediate sense. However, every crisis creates hope. It says about Yaakov Avinu, "Yaakov saw that there was shever in Egypt." (Bereishit 42:1) Shever here means food, and therefore the meaning of shever (which usually means breaking) is also the beginning of hope. Similarly, the phrase used in regards to childbirth is "sitting on the mashber" – because as a result of this predicament a child enters the world, and this is the hope and result of the pains of childbirth.

On Rosh Hashana we blow tashrat, which are tekiah, shevarim, teruah, tekiah gedola – which symbolize our life. In the beginning, everything goes smoothly like a tekiah. Afterwards begin days of crisis, and there is the turmoil of teruah. However, all this leads to the tekiah gedola; from the suffering comes the hope of a greater future. May we merit hearing the shofar of Mashiach: "Blow with a great shofar for our freedom, and bear a banner to gather our exiles."

קוד השיעור: 3842

(Translated by Rav Meir Orlian)

לשליחת שאלה או הארה בנוגע לשיעור:

.jpg)